Andrew Bernstein: The Photographer Behind Iconic NBA Photos

![]()

Andrew Bernstein is the NBA’s (National Basketball Association) chief photographer and has worked with them for the last 42 years. He has captured iconic moments with Kobe Bryant, LeBron James, Michael Jordan, and many more legends.

Andy, as everyone fondly calls him, was instrumental in creating NBA Photos in 1986 as the league’s in-house licensing agency and served as senior director until 2011. He chronicled Team USA through its 1992, 1996, and 2000 Olympic championships.

Capturing LeBron James Break the Scoring Record

Bernstein’s most recent iconic photo was of Lakers superstar LeBron James breaking Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s all-time scoring record on February 8th, 2023.

“It was very stressful because we knew he was approaching the record,” Bernstein tells PetaPixel. “When he was within striking distance, I went on high alert.

“The NBA sent me to New Orleans because he was 64 points away, and of course, he wasn’t going to score 64 points in a game [LeBron’s personal best is 61], but just in case, so that was kind of a test. And then the next one on Feb 7, 2023, was really the game that was earmarked where he needed 35 to tie and 36 to break the record of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar at 38,387 points.

“There’s a lot of preparation that goes into it. I prepare for every game, but this one was ramped up because of the moment’s significance. We set up five or six remote cameras on the opposite end of the court from where I sit.

“I have four handheld cameras in front of me. If the action was going to happen on the other end of the court, I had to make a split-second decision whether to use the handheld cameras that were in front of me or bang the remote camera button.

“I decided that if he was in the key-painted area in front of the basket where all the remote cameras are focused, I would hit the remote button. Otherwise, if he was outside of that, I would shoot it with the camera in my hand. That’s what happened, and it laid out well. [The view] wasn’t obstructed, and LeBron kind of took his time setting up for that shot.

“I only get one chance at it because I shoot with a big strobe system in the ceiling, so I can only take one picture every four seconds, and four seconds is an eternity in sports.

“Everything had to come together compositionally. I had to be in focus, obviously not get blocked by anyone, but also, the technology had to work. The strobes had to fire when I pushed the shutter button, and it all happened, so it was very gratifying that I could get a nice picture.”

Why Only One Shot at a Time?

For a sports photographer, having to live on just that one single shot is completely the opposite of how sports photography ordinarily works, but it’s the only way Bernstein has known how to shoot since he was a photo assistant four decades ago.

Sports Illustrated trained Bernstein to put these giant strobe units in the ceilings of arenas in the catwalks, and the photographers he worked for back then were used to shooting one frame at a time, whether it was on a Hasselblad or a Canon or a Nikon SLR.

In the film days, slide film was the best at 100 ISO. 400 ISO and faster films were available, and 400 ISO could be push-processed by one or two stops, but the grain got annoyingly larger, and detail and sharpness suffered, which made large prints impossible.

“That’s what I started doing when I became a professional in the early 1980s,” says Bernstein. “To this day, the NBA, as well as the NHL, the hockey league, to some extent, but the NBA exclusively uses strobe photography from their team photographers in all 30 arenas.

“I don’t know how long that will be because of newer camera technology and lighting improving in arenas.

“If you press the shutter too soon before the flash power packs have had a chance to recycle, then you risk the chance of blowing out the fuse.

“If you blew a fuse, we can’t go up on the catwalk during a game to reset the fuse on the strobe pack or the panel. You are screwed for the rest of the game.

“The lighting consists of eight 2400-watt second Speedotron [now part of PromarkBRANDS] packs, so that’s 8×2400, which is, I don’t even know what that is, you know, 20,000 watt-seconds or something. Each is attached to a quad head, so there’s one head per pack, and they’re daisy-chained together.

“When I push the trigger button, the circuit goes up to the catwalk instantaneously, and all eight strobes go off simultaneously. In that set, if you lose one, you know you could live with it if it’s not your key light; otherwise, you’re looking at shadows and cross-lighting and all kinds of weird stuff. Sometimes these sets don’t work if the chain/circuit is incomplete.

“We do use PocketWizards for radio control on the court, but with all the RF [radio frequency] noise in arenas now from the scoreboard to television to PDAs, even cell phone signals can jam up our frequency. It’s just not reliable.

“Other photographers are all shooting available light. The available light in arenas is now light years better than when I started when many had tungsten lighting. In the film days, you didn’t have a wide range of tungsten films with high sensitivity.

“It was a nightmare with film as sometimes the light was mixed — tungsten with mercury vapor. Who knows what that color temperature was?

“Now all arenas are lit with crisp, bright LEDs. I work mainly in Crypto.com Arena, which used to be Staples Center, so the available light is excellent. The caveat is that the Los Angeles Lakers bring in supplemental lighting, which is very directional and almost theatrical-looking tungsten lights.

“It’s very warm lighting, so you must know what your white balance will be. Their whole goal is to make it look a little bit like a Broadway show where the audience falls into darkness, spotlighting the court, which is the stage.

“I’m shooting at 500 ISO at 1/320th of a second because I’m hardwired into the strobes; otherwise, I’d have to shoot at 1/250th of a second. At approximately f/8, it’s clean and looks great.

“Most of the other photographers are shooting available at 4,000-5,000 ISO, 1/1000 sec, at f/2.8-4.

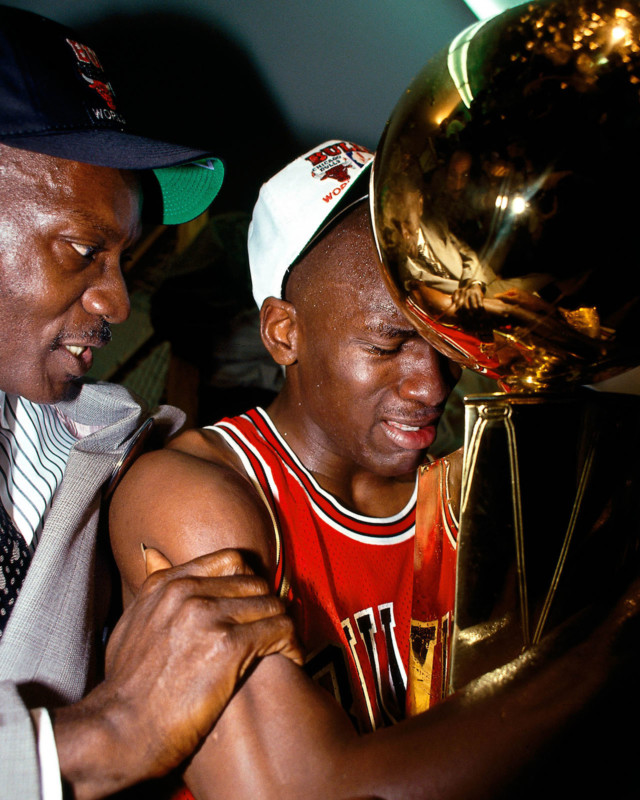

Capturing Michael Jordan Crying with the Trophy

Another of Bernstein’s most famous photos is of NBA legend Michael Jordan crying with the Larry O’Brien Championship Trophy after winning the championship in 1991.

“It’s funny because some of my more well-known photos, that one particularly, are non-action photos,” says the NBA photographer. “This was a very photojournalistic moment as I do sort of pride myself on being, first and foremost, a photojournalist.

“It was an important moment because it was Michael’s first championship which had taken him seven years to win. It was a poignant moment in the locker room with his dad beside him. His dad was tragically murdered a few years later, and there are many backstories with that photo.

“It was a very chaotic, tiny locker room situation after the Bulls had beaten the Lakers in the finals in 1991. The NBA and the network in those days used to do the trophy presentation for the winning team in the locker room.

“I jumped up on a folding table that they had in the middle of the locker room, and the network did their trophy presentation. They go to a commercial and want to come back and interview Michael Jordan live on TV. During that time, he had taken off with the trophy, so you got people screaming and yelling, and there’s champagne flying everywhere. They can’t find Michael. Something in my head said, look to your left, and I just pivoted to my left, and there he was, maybe five feet away in a locker.”

“He’d taken the trophy and tried to find some tiny little sliver of privacy and was holding the trophy with his dad next to him, and I banged off a couple of shots. Then the producer came and grabbed him for the interview.

“I was super happy that I got that moment because it was the first of his six championships, and at that time, we didn’t know. Certain photographs take on an iconic status only because of [the future] accomplishment of the athlete.”

Bernstein captured the now iconic image on a Nikon FM2 (with a then-uncommon speed range of 1 to 1/4000th second, plus a fast flash X-sync of 1/250th second) and a hot shoe flash.

“Back in those days, I was using Fujichrome, probably 100 or 400 or something,” says Bernstein. “I don’t even know, but it was definitely Fuji because we shot everything on transparency. I didn’t have the instant gratification of looking at it on the back of the camera, which we have now and didn’t know until many hours later.

“It was processed at a lab that the NBA paid to stay open all night. It was gratifying when I got that photo, but earlier, it was a little nerve-wracking not knowing what I had captured.”

When Bernstein took the photo, he had no idea whether Jordan’s eyes were closed or the trophy covered his face, etc. But he does not think that photograph’s transition to digital has helped him much in this area.

“I mean, if I missed that LeBron James shot last week, I can’t ask him to do it again, can I? Also, I might have only taken two or three frames with the Jordan shot. It was on manual focus, so I was pretty confident that I had focused it but not whether his eyes were closed or there was some crazy shadow…”

Documenting Kobe Bryant Over 20 Years

“I have spent 20 years documenting Kobe’s career,” remembers the photographer. “I literally took his first picture as a Laker, and his headshot on media day, his very first year 1996, and I took his very last picture as a Laker when he walked off the court in 2016 and probably a million photos in between, and many of them have been published.

“I documented every historic moment, all five championships, MVP awards, gold medals, a lot of behind the scenes, family stuff. But a mountain of photography was not published, so I wanted to do a tribute.

“I had this grand idea for it to be like a giant Tashen Sumo book [a 20×28 inch, 66-pound photo book that was sold with a bespoke stand in 1999 for $1,500]. I created a hand-printed and hand-stitched prototype and spent a lot of money. It was gigantic and opened to 40 inches wide.

“I made an appointment to meet with Kobe and his marketing folks at his office in Newport Beach. I gave Kobe white gloves, and he seemed to be loving it. He went through the book of 40 pages with a leather, hand-embossed cover.

“He goes through the book, and he’s not saying anything, he’s not reacting in any way, and I’m literally sweating bullets. Then he very carefully closes the cover, dramatically removes the gloves, looks up at me, and says, ‘I have some really good news and some potentially bad news. The good news is we will do a book together; the bad news is, it will not be this book.’

“From the moment I mentioned doing a project together, he knew what kind of book he wanted, and the book he wanted to do ended up being The Mamba Mentality: How I Play. He wanted to be able to tell the world what it meant to him to be the Black Mamba [based on fastest moving, venomous snake].

“The book was divided into two parts — process and craft. Process was everything it took for him to become who he was, his mental and physical preparation, and then craft was everything that was basketball related. My job was to illustrate everything he wanted to be discussed in the book, from playing defense to practicing to caring for his body and mental preparation.

“Half of Kobe’s career happened pre-digital on film, so those half a million photos of Kobe are stored at the NBA photos archive in New Jersey. I had to rely on well-trained basketball editors who went deep into the files to find things I didn’t even know existed.”

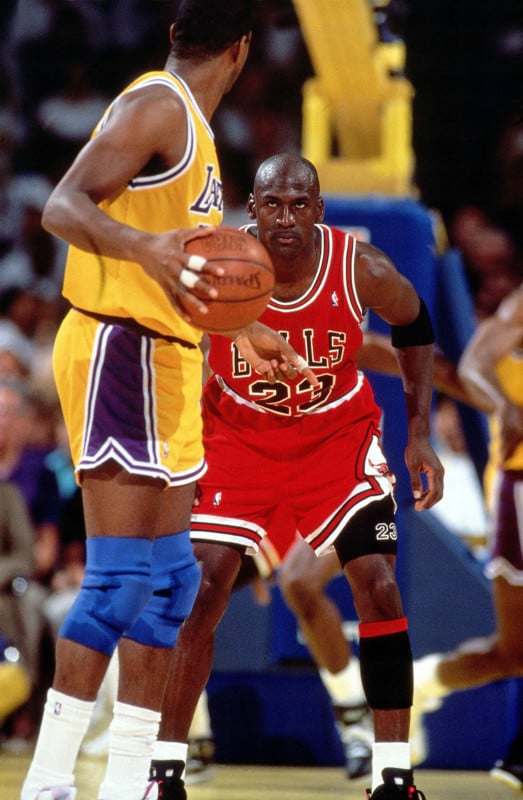

The above image was shot from a remote Hasselblad (on 120 film) with a 350mm lens suspended from the rafters at the Forum. The Forum had that beautiful Laker-gold ‘key.’ It’s uncommon to see the top of a player’s head and the bottom of his sneakers in the same shot.

The camera and lens combination was very heavy and had to be mounted on the rail of the catwalk pointing down, so it had two or three different connection points for Manfrotto Magic Arms, and there were Magic Arms supporting the Magic Arms, so it was rock solid, and everything was safety cabled.

“I was good friends with the lab owner and had dropped the film off the night after the game on my way home,” remembers Bernstein. I go back there at 8.30 in the morning, and it’s hanging in the dryer, and there’s only one roll of film because I can’t change film at halftime. I see it, and then boom, there it is. It’s almost like the sun came out.

“It was the most perfectly timed composed image I think I’d ever taken by a remote camera at that point. I was so excited that I made him a huge [50×70 inches] print, framed it, drove it up to his house, and I think Vanessa, his wife, still has that hanging somewhere. At that time, Kobe was still a teenager living with his parents in Pacific Palisades.”

Another of Bernstein’s favorite Kobe images is when he found him icing his ankles in a cooler with his finger in a little cup of ice before a game against the New York Knicks at Madison Square Garden in January 2010. Coach Phil Jackson called this ‘The Thinker,’ like Rodin’s sculpture.

In 2009-10 Bernstein collaborated with coach Phil Jackson, who has won a record 11 NBA titles, on a book, Journey to the Ring. Jackson was a good amateur photographer and wanted the book to be in black and white, and Bernstein was all for that. The photographer was given access to the Lakers’ on and off the court, resulting in a beautiful four-color black and white processed book of the Lakers winning the championship over the Boston Celtics.

LeBron and Shooting from the Hole in the Pole

In 2020, a photo by Bernstein of LeBron soaring for a reverse windmill dunk against the Rockets went viral. It was LeBron in his 17th year, and people had not seen him dunk like that as the young LeBron used to.

“When we do this system of five or six remote cameras in strategic areas around the court, one of the cameras is looking through the backboard of the glass with a 24mm lens, another is on the stanchion horizontally, and other ones on a railing,” explains Bernstein. “There’s one overhead looking straight down. We even have a camera with a 300mm lens on a tripod way back in the TV position, looking at the basket through the crowd.

“But one of my favorite remote positions was always putting a camera, usually a Hasselblad, on the floor and having an assistant sitting next to it where the photographers sit. This floor remote captured the LeBron shot above. You see two giant strobe bursts going off on either side of the scoreboard in that photo.

“If a player was coming towards the floor camera, the assistant would pull it up and get it out of the way so the player wouldn’t trip over it. Unfortunately, players were running into these cameras, and one player got hurt during the finals game, and after that, the NBA said no more of what we used to call floor remotes.

“I was mortified that entire summer because that was one of my favorite angles where I had gotten many great pictures. If you see a basketball stanchion, the front extension is a pad about eight to ten inches thick to protect a player who might run into it. Behind the pad at the bottom part, it is hollow. So, I thought I could cut a hole in the bottom of the pad just big enough to insert the camera on the floor.

“I approached my boss at Staples Center, who thought I was crazy, but he let me try it in the preseason. They liked it, and it was green-lighted and became what is now called the mouse hole or floor camera.

“Now it’s done with 35mm, and I believe it is a Nikon D850 camera with a 24mm lens. What makes me the happiest is that TV cannot do that angle as they don’t have a camera small enough to fit in the hole to copy what we do. Now in any NBA arena, it’s standard practice to manufacture basket pads with the hole in it on both baskets. It will live on after me – the Andy Hole! I should have patented it. I could have retired with that.”

Remote Cameras and Remote Lighting

All those remote cameras are manually focused and taped down. They are focused on the front of the basket’s rim, so if any action happens within 12 to 18 inches of the rim where the depth of field is, it will get a sharp photo of the action.

“That’s when I hit the button when all those remotes go off, and all the eight cameras fire and are all synced to the same strobe system,” explains the basketball shooter. “What’s fascinating about this technology is that it is all done by radio. The radios must talk to one another, and all will be firing and opening the shutters of their cameras simultaneously, the exact millisecond that the strobes are bursting, right, so you think?

“In a gigantic arena with so much RF and interference noise, it’s incredible it works. It’s called the FlashWizard II, designed by Lab Partners Associates (LPA Design), the same company as PocketWizard.

“These guys reached out to us in 1997-98 and had this crazy idea, and it took us a couple of years of R&D to get it to work, but it’s become the standard now. The FlashWizard II is no longer produced, and you can’t even get them fixed. Photographers now use the PocketWizard to do multiple camera remote systems.”

Four Decades of Change in NBA Photography

“Going from film to digital has been the biggest change,” says Bernstein regarding how basketball photography has evolved over the years. “I still prepare for games the same way I always have, so my process hasn’t changed with the technology. We no longer have to reload cameras; we no longer have to keep track of film counts, especially on remotes. We used to do a lot of remote cameras using Hasselblad with a 24 exposure back, so I knew that I couldn’t change film until halftime. That limited me to 24 images I could bang off and not run out of film.

![]()

“If you look at old footage of the NBA finals or playoff games, you see probably 60 photographers on the court. Now there are 12 photographers total on the entire court.

“The NBA has been very careful to take care of players’ safety and always has in mind that players are less likely to fall onto and trip over with fewer people.

“So, I’m lucky to be one of the last remaining people on the court. Everyone else now has had to go to an elevated position which, of course, is a different kind of photography. I prefer to be in the trenches and have it [the players] come towards me rather than be a lateral kind of just follow the ball.”

Bernstein’s Choice of Camera Gear

Bernstein has four handheld cameras with four different lenses on them. The Nikon D5 and Nikon D6 cameras are plugged directly into the strobe system, meaning a wire [a PC flash sync cord] goes from the camera up to the ceiling into the strobes.

“One is primarily for the near court where I use an AF-S NIKKOR 28-300mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR, and on the down court, I’m using the AF-S NIKKOR 80-400mm f/4.5-5.6G ED VR to shoot things on the other side of the court,” he says.

“The other two cameras are D4s’ what I call my walkabout cameras with a PocketWizard attached. I walk around and get the huddle shot, the celebrity shot, or whatever I have to do on the court and be mobile. On those D4s’ I’m using an AF-S Zoom-NIKKOR 17-35mm f/2.8D IF-ED on one and usually an AF-S NIKKOR 70-200mm f/2.8E FL ED VR on the other.

“Once the game starts, I’m not using those two Nikon D4S cameras except at the end of the game when I must run onto the court and shoot whatever interviews are going on, or sometimes, I have to go around the court during the game and shoot celebrities or whatever’s going on.

“The two hardwired-to-the-strobes-cameras (D5 and D6) are also connected to an ethernet line plugged into each camera. As I’m shooting, the images go through a high-speed HSAN2 (high-speed arena network) line back to an editor in Secaucus, New Jersey, at NBA photos. The editor receives my photos in realtime and can make selections, [add] captions, and upload them to Getty Images.

“So, what we do at the NBA is as close to live coverage as possible. Photos are posted to Getty within a couple of minutes of the action.

“I shoot RAW and JPEG on the same card with a backup card in the camera. We use Sony XQD cards. We’re transmitting the JPEGS, and the RAWs are kept in case we need them. So, they are downloaded onto a hard drive.”

Bernstein is not interested in upgrading to the latest and greatest of the mirrorless world in the Nikon Z9, as the current system has served him well.

“You know, I got to tell you, my friend, that everybody’s using them, and everybody’s trying to get me [to use them],” he admits. “I’m kind of, you know, trying to take a little step away from the court. I’ve been doing this long, and the end is in sight. I don’t want to learn or buy a whole new camera system. Quite frankly, it’s beautiful, it’s wonderful, and I’m used to what I have. I’m an old dog who doesn’t like learning new tricks.”

Getting Into Photography and Specializing in Sports

Bernstein arrived at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California, from the University of Massachusetts, where he did all kinds of photography. They had a daily paper at UMass, so he was doing news, features, and sports.

While attending the University of Massachusetts Amherst, he built a portfolio that earned him a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship and a scholarship to attend ArtCenter.

“I didn’t know which part of photojournalism I wanted to get into, but I very quickly decided it had to be in sports, especially when I started assisting Sports Illustrated photographers and saw how exciting it was on the job,” Bernstein says.

“I had some visions of being a documentary film cameraman or something, but I just didn’t ever want to go to war. So, I chose to be on the playing field rather than on a battlefield!”

Bernstein has had a fun ride with the NBA covering anything and everything, including photographing Shaquille O’Neal from the wheel well of his Lamborghini with the speakers blasting in his ear while Shaq drove at 95mph on the Florida Turnpike.

“Now I mentor young photographers who we are trying to bring into the fold — the next generation. I take that very seriously, and I enjoy that a lot and am still out there shooting.

“They’ve been very gracious with allowing me to scale back on the work I must do. I am not traveling, maybe very infrequently, and I only do half the home games now, which has been a blessing.

You can see more of Andrew D. Bernstein’s work on his website and Instagram or join him on his podcast or in a workshop.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: All photos courtesy Andrew D. Bernstein/ NBA and Getty. Copyright NBAE.