Roger Deakins: Legendary Cinematographer with a Photographer’s Eye

![]()

Sir Roger A. Deakins is widely considered to be one of the greatest cinematographers of all time. He has won two Academy Awards and sixteen nominations for his cinematography of over 70 feature films.

Deakins (born 1949) has spent much of his career encircled by film sets. He finds working on movies as a cinematographer to be stressful. This demanding environment does not get any better with experience, involving collaboration and coordination with the director, actors, and various crew.

On the other hand, photography is genuinely independent. It provides him with a sort of release and relaxation from the stress of work – whether on the weekend off or in between shoots as director of photography. He has shot B&W photos from Bristol to Berlin to Budapest.

“My process is pretty straightforward,” Deakins tells PetaPixel. “I enjoy walking and exploring new and also familiar places. Sometimes I see an image that seems to strike me as interesting, but more often, I can spend hours just observing without shooting a single frame.

“What can I say? It [photography] really is not something I analyze. I love finding images.”

Unlike his meticulously planned screenwork, his black-and-white shots are casual street photographs. He does not have very many negatives, and with digital, he erases whatever he does not like. And firstly, he is not a prolific shooter. Even when he goes out intending to take photos, he often returns home without a single image.

Deakins studied photography at an art college in Bath (west of London, England) but does not necessarily apply the rules of photography to his filmmaking.

“I am familiar with the ‘rule of thirds’, but I have not considered it a conscious part of my approach since I attended art college in the 1960s,” he says.

“I always loved painting since I was very young, but it was not until I was at Bath Academy that I looked to photography to express my thoughts. How did it happen? I suspect my paintings were quite naturalistic, which was out of fashion in the 1960s.”

“There are probably a few painters whose work has inspired me more than photographers. There are so many great photographers and image makers that mentioning only one or two would be too simplistic.”

Color is a Distraction

Although Deakins has published Byways, a collection of his 50 years of street photography, he has no secret sauce on the subject.

“I can’t say anything is important about street photography,” says the photographer. “Whatever is important to one person may be of no consequence to another. That is what makes the photographic image interesting. We all have a different ‘eye.’

The one thing that strikes the viewer is that Deakins’ cinematography is in vivid color, but his personal photography is all in B&W.

“I used to develop my own film, and I always loved the simplicity of a B&W image,” explains Deakins.

“Color can be pleasing and vibrant and be about nothing but itself. It can complicate an image, and I am always striving for simplicity.

“I find color a distraction to the ideas within a frame, though, that said, there are some great photographers who work in color. I just can’t.”

Deakins grew up inspired by the classic black-and-white images of photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Dorothea Lange, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Bill Brandt.

The celebrated director of photography does shoot color photos on his digital cameras but finds that they become more powerful when he converts them to B&W.

Cinematography and photography are entirely independent, with no connection between the two for Deakins.

“They are very different ways of seeing,” he clarifies. “My still photographs are my personal sketches that either stand or fall on their own. What I do as a cinematographer is so very different.”

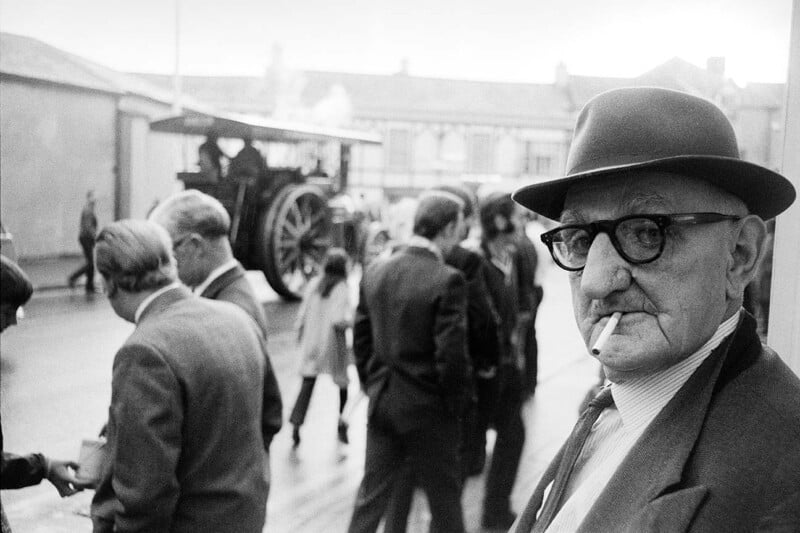

The B&W Photographs

Deakins remembers taking his first photograph in 1969 in Bournemouth, England. A man and a woman are eating lunch on a bench outside a ladies’ room with a sign that says, “Keep it to Yourself.”

“I used to hitchhike to various locations and spend the day with my camera,” recounts the cinematographer of the twenty-third Bond film, Skyfall. “Sometimes, I even slept on the beach to catch the early light.

“The photograph [referenced] was taken one day when I had made my way to Bournemouth and was just walking the promenade. What attracted me to the image was the juxtaposition of the elements in the frame, the older couple with their lunch, the restroom and the sign ‘Keep it to Yourself.’

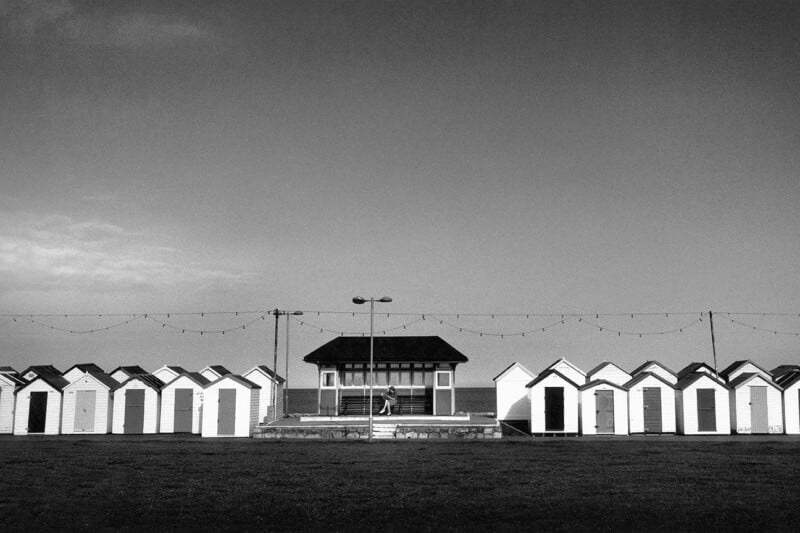

Deakins tells The Guardian, “I returned to it [the scene at the seaside in 2004] throughout the day and took variations of this shot, but none were as strong. I didn’t speak to the woman here – I rarely make conversation when I’m taking photographs – but she gave me a kind of wordless nod after looking at me and wondering what on earth I was doing.

“Just as I went to take the photograph, she looked across at the poster. It was the perfect moment. I loved the juxtaposition of this elderly lady holding her umbrella at the height of the British summer, contrasting with the semi-naked young woman lying in the sunshine on a boardwalk. I liked the age gap between the two.”

In the foreword to his Byways book, Deakins questions, “Whether without a detailed explanation of how and why a picture came about, can it mean the same to the viewer as it does to the photographer?

“Knowing that the image of the eagle was taken in Romania and is of a statue that stands sentinel over a German war grave can only change the relationship between the photograph and the viewer.”

This shot was taken of Salisbury Plain (central southern England) at dusk at the end of a scouting day for locations, and the tree is shown at the end of the film 1917. The film, which netted Deakins his second Oscar for Cinematography, is created to look like the whole movie is just one uninterrupted take or shot without any cuts, thanks to the artistry of DP Deakins and director Sam Mendes.

Deakins has the patience to wait months for a photo. He lived a few miles from this cliff and jogged the path. He waited for winter when the tree would be bare.

When he found that they cut down the bracken and the tree had opened, he saw his chance and captured varying images with different skies. But the one he loved was the one with the plain bright sky right behind the tree and the light shining off the water.

Many images in his photographic oeuvre have harsh lighting, and Deakins also uses it in his cinematography, but it is finely controlled. In his latest film Empire of Light, there is a scene when harsh lighting is required to show a character’s raging paranoia.

Deakins took the shade off a table lamp and used a bare bulb. The harsh light almost bleaches out the face of the actor, but it is still well controlled. The DP stuck a piece of tape on the side of the bulb facing the camera so that it would not flare the lens, which he hates.

When Deakins shot the Coen brothers’ film O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) in Mississippi, it was a lush green. But the look that was desired was an autumnal yellow. The DP spent a couple of months fine-tuning the look and desaturating the entire image. This resulted in it being the first feature film that was digitally color-corrected in its entirety and earned him his fourth Academy Award nod for a nomination.

A person was throwing a stick off the promenade, and the dog jumped after it. Deakins got into a position and waited for him to throw it again. He shot from a low angle, and just as the shutter clicked, luckily, the dog looked at his camera.

“The Joy of Flight is a very simple photograph,” says the Englishman. “It is easily read, and I think it works as a small image.” [Referring to Magnum Photos using it for their last print sale.]

Denis Villeneuve’s Sicario was shot in New Mexico. At the end of the shooting day, Deakins would take off with his trusted still camera looking for the last traces of light. Sometimes he would drive to the same location and wait for late-day thunderstorms to produce the shot he visualized like the lightning bolt.

For the lightning strike bisecting the building, Deakins let the shutter click away and luckily landed the perfect frame.

Still Cameras and Movie (Video) Cameras

Deakins’ first camera was a Praktica film SLR. The digital camera he has used the most is the Leica M8. The movie/video camera he has relied on the most in the last five years is the Arri Alexa LF (sensor slightly larger than full frame).

“An Alexa LF…I like the image it produces, and I like the way it fits me as an operator,” says the cinematographer.

Deakins, knighted in 2013 for his service to film, is not much of a gearhead who desires the latest and greatest features in his cameras.

“[Camera features] would depend on the project in hand,” he says. “I don’t need many of the additional features that are being built into newer camera systems. That is why I love the Leica M8 or M9 cameras. They are really simple manual cameras.”

Deakins has also used the Nikon F3 and the Leica M6, which PetaPixel selected as one of “the Best 35mm Film Cameras of All Time.” He owns two Leica M9 cameras, one of which is monochrome and his favorite camera.

Although the cinematographer uses some of the most expensive and advanced cameras in his professional work, he is not dismissive of the humble cell phone camera.

“You can create an image in any way you want,” he says. “The subject and the framing are more important than the means of capture.”

Deakins often uses a still camera on movie sets to record the environment.

“I simply use a still camera to record an image of a location or a set so that I can then use it as a reference,” he says. “These photos … are only spacial references [and not to examine the lighting].”

Today’s small mirrorless cameras can produce high-quality video, but Deakins does not believe this can lead to an increased interest in filmmaking/cinematography by still photographers.

“Shooting a film is so different from capturing a single still frame,” explains the master. “I don’t see why there would be any more or less crossover simply through a change in technology and camera size in particular. Ansel Adams’ still camera was pretty big!”

“I think there are many ways to find and explore filmmaking,” he says. “Perhaps photography offers a way in, but I also know renowned stills photographers who started out as filmmakers.”

In the older days of movie making with film, the director and others couldn’t view what the cinematographer was capturing, so “dailies” were created. These were the first positive prints from the negative photographed the previous day and viewed by the director, actors, and crew.

“There are advantages as well as disadvantages,” says Deakins. “The technology itself is not at fault, but how it is used is important.

“Personally, I like showing a director what I am thinking and what the image looks like rather than waiting for any comments they might have in the dailies screening room the next day.” [The reference here is to the monitors where the director can see what the cinematographer is capturing in real time.]

The Beginnings in England

Deakins never planned on becoming a cinematographer. His first passion was photography. He finished art school in Bath and then worked for a small arts center in North Devon. His job was to photograph local scenes. It was then that the National Film School opened.

“After I discovered a love for a photographic image, it seemed natural to explore whether documentary filmmaking might be another avenue of exploration,” remembers Deakins. “Only when The National Film and Television School opened up, did I see an opportunity in that direction.”

Deakins got a spot on the second attempt, which moved his life and career toward cinematography.

The DP had initially been interested in documentary photography, so he worked on the same genre of documentaries as a budding cinematographer. Some directors asked him to work on fiction films and he gladly obliged. When no more work was found in London, he landed a movie in the US. Next, he was approached by the Coen Brothers (Fargo, The Big Lebowski, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, No Country for Old Men), and the rest, as they say, is history.

Deakins has still not been able to forget his attraction for the British seaside, despite living for many years in Santa Monica, California. He grew up in Torquay, a seaside town on the southern edge of England. The history and nostalgia of the Victorian and Gregorian structures still linger in his mind.

Deakins never intended to exhibit his photographs which was just a personal hobby for him. During COVID and lockdown, he sat down with his wife, James (Isabella James Purefoy Ellis, referred to simply as James), to compile a record, which led to a book. Byways, his first photo book has been successful with requests for exhibitions worldwide. So, maybe we will see a second offering from the master cinematographer.

You can see more of Roger Deakins’ photos on his website.

Byways (Damiani) has a large collection of Deakins’ B&W photos.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: All photos © Roger Deakins. Header photo: Sir Roger Deakins portrait © Misan Harriman; The Joy of Flight – Teignmouth, 2000 © Sir Roger Deakins. This image was selected by Magnum Photos as part of its recently concluded Magnum and Friends print sale.